| Mon | Tue | Wed | Thu | Fri | Sat | Sun |

|---|

American tech giants are invoking the Chinese specter to avoid any regulation. Yet the United States enjoys a massive advantage in computing power, energy, and talent.

For some time now, a narrative has taken hold in Western capitals, particularly in the United States. We are repeatedly told that the West is engaged in a frantic race against China to dominate artificial intelligence, and that losing this race would have catastrophic consequences for our societies and values. This narrative is simple, anxiety-inducing, and effective—but it contains a major flaw: it does not reflect the global technological reality. Instead, it may serve other interests.

First, let us try to understand where we stand. According to several studies, including those by D. Kokotajlo, progress in AI rests on three pillars. The first is “compute,” the raw computing capacity required to train advanced models. The second is access to abundant and stable energy, since each new generation of models consumes ever-increasing amounts of electricity. The third is human talent, indispensable for designing, fine-tuning, and supervising these systems. Without compute, no models. Without energy, no compute. Without talent, no progress. And on all three pillars, the United States currently enjoys a massive structural advantage.

Artificial intelligence

The United States possesses roughly five times more computing power than China, largely thanks to Taiwan, where TSMC manufactures the world’s most advanced chips using American equipment. Without these components, China cannot train comparable models. The American advantage also rests on energy. Its vast energy mix allows it to power data centers at costs well below those of China or Europe. The United States also has underutilized gas power plants that can be mobilized quickly. China, by contrast, remains constrained by local grid saturation and a heavy reliance on coal. As for talent, leading AI researchers are primarily based in the United States, which attracts top profiles trained in Europe, India, or China.

U.S. tech leaders speak of an existential threat and claim that any regulation would mean losing the race, while deploying massive lobbying efforts. This rhetoric is not without echoes of the Cold War, when the military-industrial complex amplified Soviet power to secure budgets. Presenting AI as vital makes it possible to capture public contracts while weakening democratic safeguards.

The confrontation is less between Washington and Beijing than between industry giants and democratic institutions. In California, the ambitious SB 1047 bill was buried under industry pressure and replaced by the TFAIA (Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act), a hollowed-out version that changes almost nothing in corporate practices. Yet the risks are real. Industry leaders themselves acknowledge that an uncontrolled AI could threaten global security, with Sam Altman even evoking an extinction-level risk. How, then, can a strategy that accelerates this race while undermining democracy be justified?

Switzerland does not need to imitate U.S. deregulation or Asian rigidity. It can choose a clear technological path: invest in compute, secure energy supplies, attract talent, independently test models, and require a minimum level of transparency. This is how an open and liberal country can regulate AI without stifling it—by strengthening both trust and innovation.Et si la vraie menace de l’IA ne venait pas de «l’autre»?

Guest contributor: Nicolas Ramseier, President of the Geneva Center for Neutrality.

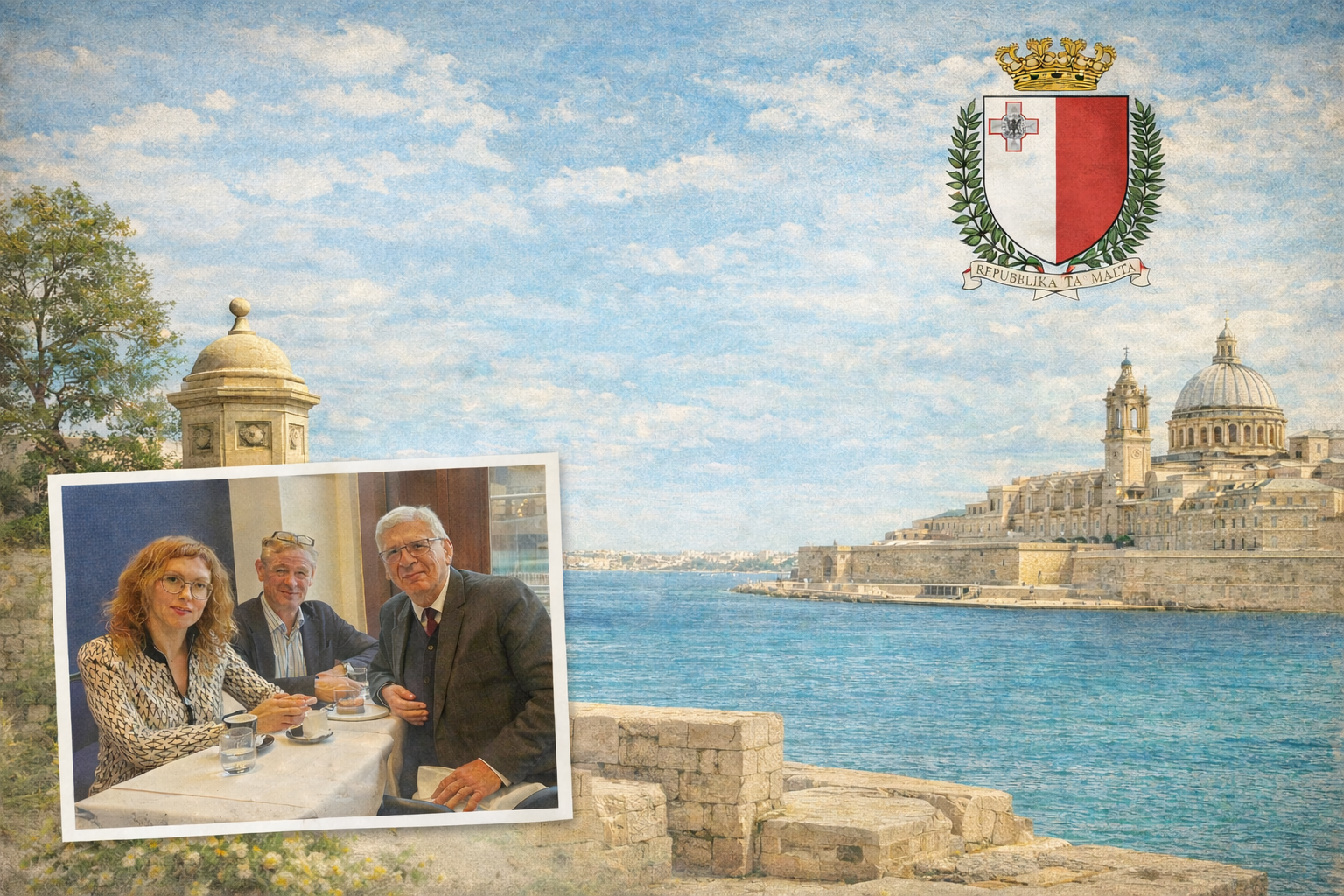

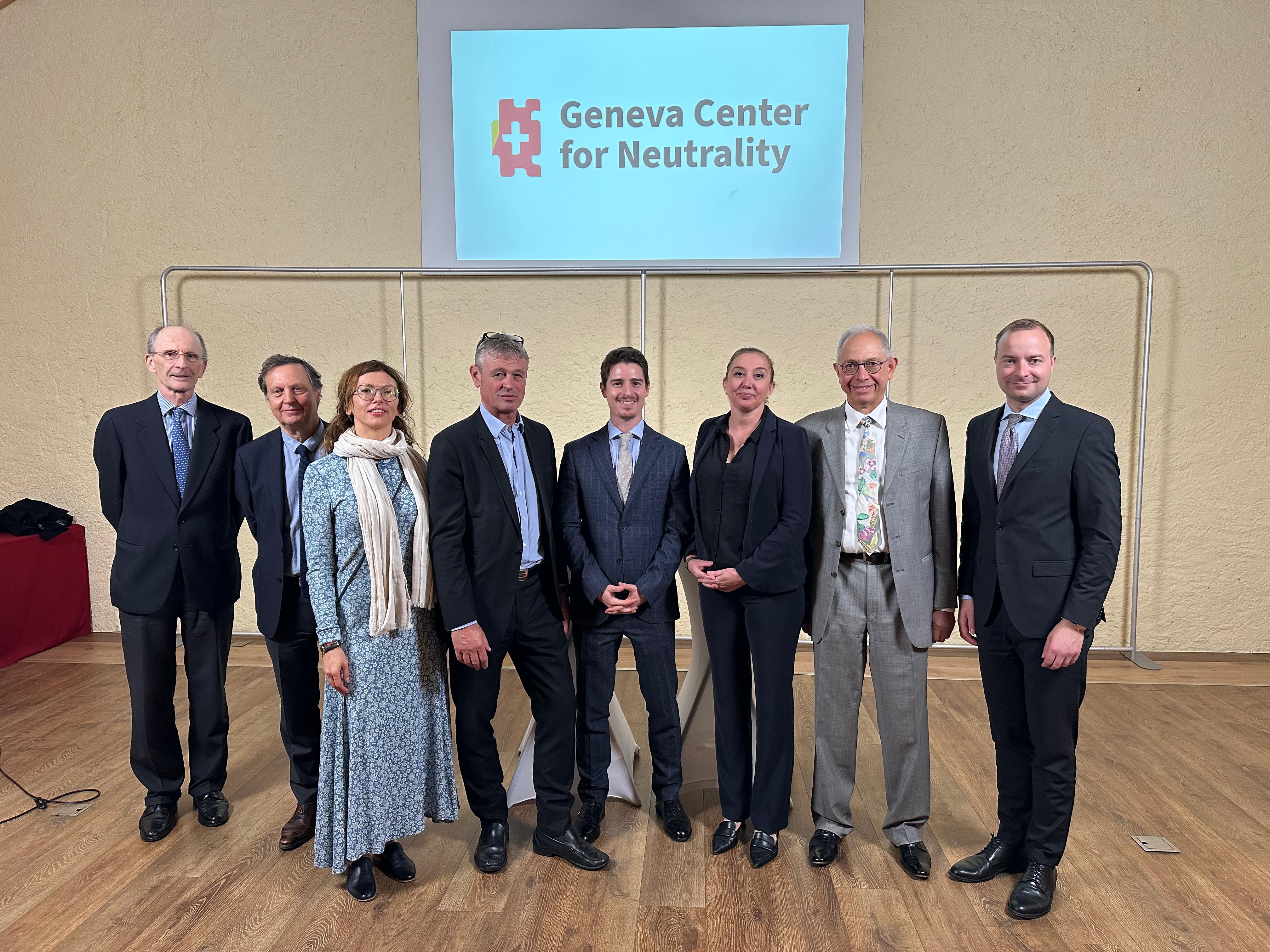

The Geneva Centre for Neutrality (GCN) recently convened a meeting in Geneva bringing together Jean-Daniel Ruch, Co-Founder of the GCN, Alexander Sceberras Trigona, former Foreign Minister of Malta and a central architect of Malta’s constitutional neutrality, and Katy Cojuhari, Head of International Cooperation at the GCN.

The exchange focused on contemporary neutrality in general and current practice in Switzerland and Malta, as well as its relevance and application in other countries amid growing global tensions. Participants underscored the corresponding increase in the value of neutrality as an active and constructive policy choice - one that can contribute more credibly to preventive diplomacy, mediation, and the peaceful settlement of disputes.

The discussion built on recent reflections by Dr. Trigona, including his presentation at King’s College, London on Active Neutrality: The Strategic Role of Neutral States in an Age of Conflict, delivered alongside the Ambassadors of Ireland and Austria. There, he outlined the Prospects for Neutrality calling for closer collaboration among neutral states and with partners such as the GCN - whether as a nascent “Club of Neutrals” or through individual efforts.

Among the proposals he highlighted were:

Strengthening engagement with the United Nations. Promoting a close and friendly working liaison between neutral states and the United Nations, including support for the UN Secretary-General and relevant offices such as the Mediation Department, in line with Chapter VI of the UN Charter on the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes and UN General Assembly Resolution 71/275 (2017), which specifically encourages the constructive role of neutral states.

Establishing an Annual Neutrality Index/Neutrality Yearbook. Publishing a regular, descriptive monitoring tool assessing the performance of formally neutral and effectively neutral states, as well as the conduct of third states in their relations with them. The Index would document the dynamism of external pressures - diplomatic or otherwise - faced regularly by neutral states and their own strategic responses thereto, as a tangible contribution to peace.

Updating the Hague Neutrality Framework. Launching an academic and policy review, initially with legal and international relations scholars, to modernize the neutrality provisions of the Hague Conventions and related instruments. This preparatory work would pave the way toward a future UN-mandated Hague Review Conference and the adoption of a “Hague II Neutrality Protocol.”

These reflections also echoed Dr. Trigona’s earlier academic contribution at Kyoto University, where he presented a historical paper on “Codifying Malta’s Neutrality” at the conference Reimagining Neutrality & its Research

In that context, he specifically recommended bringing the process of updating the Hague Conventions back to Geneva - by institutionally linking such efforts with the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs and the Conference on Disarmament—thereby returning to the historical roots of the Hague framework with a renewed commitment to peace. The meeting concluded with a shared assessment that 2026 will be a pivotal year for deepening work on neutrality.

On December 12, marking the International Day of Neutrality, the International Institute for Global Analyses released an overview in its Analytical Dossier, examining contemporary world dynamics with particular attention to the concept of neutrality: Life in the «buffer zones» and Neutrality Alliance

Is Trump relying on a form of transactional diplomacy aimed at engaging China and Russia in a global governance system shaped primarily by the interests of these three major powers? It looks like the consensus among them has yet to be reached. Medium-sized states are scrambling to balance relations with all three powers, hoping to protect their vital national interests. Small states, especially those stranded in geopolitical buffer zones, have it even worse: being forced to choose sides. In this polarization, countries with traditions of neutrality, and those now adopting pro-neutrality policy as a survival strategy, are becoming more and more important.

Swiss neutrality: questioned, but not lost

The Swiss version of neutrality is often held up as an example for other nations to follow – those that do not wish to be absorbed into the spheres of influence of one of the three superpowers. Swiss neutrality was born in the middle ages through a combination of geography and the independent spirit of the country’s citizens. Powerful monarchies on all sides could have overwhelmed the Helvetians but did not believe the prize was worth the effort it would have taken to break Swiss spirit. While never rich in those early days, Switzerland provided a trading hub and a source of military manpower for its big neighbors and managed to survive independently of the European empires.

Switzerland’s status as a formally neutral state was strongly reinforced at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when the European powers and Russia, decided that it would be in their own interest and in the interest of the concert of Europe to insist on and codify Swiss neutrality, keeping Switzerland out of the hands of rivals and providing for a space free from their continuing competition. The decision to attach Geneva to the Confederation in 1815 added over time several important new dimensions to Swiss neutrality – an openness to refugees, a safe space for savants, a focus on humanitarian action, conventions and institutions that grew into a would-be supranational system of world governance, intergovernmental arbitration, multilateralism writ large and, most visibly, a home for what was designed to be the first world government, the League of Nations.

It was not just Geneva. By the end of the nineteenth century, hydroelectric power kick-started Swiss industry. Switzerland’s determination to be able to defend itself against all potential enemies led in time to a vigorous arms export sector – tous azimuths. The Federal government early on went into the business of providing “good offices” to maintain communication between mutually hostile states. Zurich contributed bank secrecy. The Cold War enhanced the role of Switzerland, especially Geneva, as the meeting place of great powers.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, Swiss neutrality has suffered severe blows. Superpower competition is no longer confined to Europe. Europe, including Switzerland, has tucked itself under the wing of the Americans, the same Americans whose attention has shifted toward China and a reemergent Russia. Switzerland finds itself not at the neutral center of competing powers but incorporated into one of them – the West. Bank secrecy has been partly abolished. The arms trade is curtailed. Multilateralism and the institutions that embody it are increasingly discredited. Respect for humanitarian law has become an attribute of small states, while the big ones prefer Realpolitik. Some Swiss favor joining the European Union and in any case follow the EU lead, as in sanctioning Russia. At the same time, other countries are stepping up as rivals in the business of facilitating dialogue. To be sure, all is not lost. Some Swiss are trying to hang on their neutrality and even enhance it. One of the examples - through becoming a neutral hub for data storage. The arc of Swiss neutrality – a noble history and tradition, what it might means in the twenty-first century context? Much will be decided by a national referendum in near future on Switzerland's neutrality.

Strategic independence with the neutrality elements

Today, all around the world, many countries are seeking to avoid having to join one superpower block. They aspire trying to reach the strategic independence – non-alignment, with pro-neutrality elements. But the option is not available to every country. Those that lie squarely within the sphere of influence of a superpower will be obliged to follow its lead, happily or grudgingly. Costa Rica, who is neutral by Constitution, for example, is free to state its aspirations but will be compelled to yield to the United States on any important strategic question. The same applies to Belarus vis-à-vis Russia or North Korea vis-à-vis China.

The nations that can legitimately hope for strategic independence are those that lie between the spheres of influence of the superpowers and try to write their own foreign policies, within limits, by playing off the superpowers and acting as a buffer between them.

India has been playing the game of strategic independence since 1947 and is likely to continue on this non-alignment line. Its traditional ties to Russia are still strong and Modi has worked for better relations with both the USA and China. Because of its size and growing wealth, India may be tempted to enter the ranks of the superpowers, but it will confront two major problems if it pursues that strategy – the fierce opposition of Pakistan to any Indian moves that would further tilt the balance of power in the subcontinent and the resistance of the Big Three to allowing India to amass the large nuclear arsenal that is a necessary component of superpower status.

The Near and Middle East has been for centuries a focal point of major power rivalry. Today the Big Three all seem to be on a different line. While hoping to exploit the wealth of the region economically, neither the USA, nor China, nor Russia seems inclined to operate geo-strategically in the region any longer than some may have to. Rather all three seem to want influence and trade without responsibility or reckless desire for change. This means that once Israel is protected by the Abraham Accords, the region should be free to pursue strategic independence, tailoring its relationships to the superpowers to fit its own interests. Interestingly, this same logic could soon apply to Iran, to whom the idea of neutrality is not acceptable today, but for the future may serve as the solution for it and for China, USA and Russia. Same for Lebanon, where the idea of neutrality seems to be utopian today, but there are forces, straggling for it now. Already China and Saudi Arabia are dealing with each other in ways that would have been inconceivable only a few years ago, and pragmatic neutrality appeared in the international vocabular today. Qatar has become a major locus of diplomacy and mediation, along the lines of the Swiss model, but at the same time hosts a major US military base, not really consistent with the Swiss pattern of neutrality, but compatible with strategic independence. The UAE would like to emulate Qatar.

Other lessons in strategic independence can be drawn from the nations that surround China. These are the very actors that the USA will need in any policy of slowing and containing China’s growth. At the same time they all depend heavily on China for trade and technology. If these countries wish to preserve their security and economic strength, they will be obliged to accommodate the interest of both China and the USA. East Asian countries, Australia included, would prefer to have it both ways, preserving the status quo. But if China pushes hard, its neighbors will be forced to choose between the security provided by the USA and the prosperity that depends, to a large extent, on China. The idea of neutrality for the countries surrounded China could be a solution, which will reduce tensions in the region.

In Central Asia the shift away from Russia began immediately after the breakup of the Soviet Union, though the historical and cultural ties remain strong. China’s Belt and Road strategy aims directly at Central Asia and beyond, providing a second strong pole of attraction for countries of the region. Turkey under Erdogan aspires to increased influence, especially in those countries speaking a Turkic language. This conjunction, coupled with dynamic economic development, should allow central Asian governments to implement – carefully – policies of strategic independence. At the same time Turkmenistan, whose neutral status was recognized by the UN General Assembly in 1995, maintains equal relations with all countries, cooperating with China, Russia, the US, the EU, and Iran without taking sides. This allows it to diversify its foreign policy and economic partnerships, benefiting from competition between major powers. Its neutral status increases investor and partner confidence in energy transportation and helps it act as a “bridge” between Asia and Europe along energy and transport routes. Turkmenistan’s internationalized neutrality through the UN, supported by economic diplomacy, has become an international brand of predictability.

African nations have largely succeeded in loosening the ties that bound them to the European colonial powers. China has moved in strongly, creating new infrastructure, and long term debt, as well as acquiring land for agriculture. Russia has experimented, mostly unsuccessfully, with military support to governments and rebels. US interests are limited to commerce and occasional peacemaking initiatives. In this climate, there is scope for strategic independence in some cases with neutrality elements, or at least room for bargaining.

European stability and Neutrality Alliance

The situation in Eastern Europe is complicated. Ukraine in a way illustrates the dangers posed by a situation where there is no buffer between two powers. Hundreds of thousands of deaths and a devastated country as a result of the competition between the West and Russia on that territory. Russia has made recognized neutrality for Ukraine one of its key conditions for ending the war and the USA would certainly go along with this element of a solution, but many of the European NATO countries would not. This question is on the table on the peace negotiations.

Moldova has always suffered from being historically held «hostage» to a “gray” or buffer zone, unable to capitalize on its position. Situated on the fault line between the EU and Russia, directly bordering Ukraine, where the war continues, it remains vulnerable to external pressure and internal instability. Its constitution enshrines neutrality, the result of domestic political consensus in 1994. Today 78% of population believe neutrality is in Moldova’s national interest, capable of serving as a guarantee of peace, according to polls conducted in 2025, shows the society mood, tired of energy and economic crises. Moldova’s European integration looks like accelerated, but the current government views neutrality as a constitutional obstacle on the path to EU membership, which in practice is not the case. Austria is a good example. Moldovan government is also increasing defense spending, even though more than a third of republic population lives in absolute poverty.

In Austria, neutrality is central to its identity. This concept, as in Switzerland, has a distinctly positive connotation. However, in reality, the country faces a complex European security environment, driven by the protracted war in Ukraine, pressure on neutrality from the growing great power rivalry, and rising EU expectations for defense cooperation. Keeping in mind, that thanks to neutrality Vienna became a diplomatic hub, a world-class venue for the UN Office, the OSCE, OPEC, etc. after joining the EU, Austria maintained its neutrality. Today, still 75% of the Austrian population supports the country remaining neutral. Perhaps by strengthening Austria's role as an international platform, forming a network of conflict mediation partners (Switzerland, UN) and adopting a renewed concept of active neutrality, Austria could significantly strengthen its security and influence in the EU.

Hungary experiences isolation within the EU, but pragmatically pursues its national interests. “Eastern European outlier” can hardly be called Putin's friend, as it votes for sanctions against Russia, but negotiates with Trump so that they do not affect Hungary. Orbán's policy could be described as a fight for a strategic independence and economic interests with elements of neutrality within the EU.

This partly applies to Georgia, an Eastern European country perceived as pro-Russian. But it is really the case, if diplomatic relations have not yet been established between Russia and Georgia? However, by maintaining trade relations with China, the US, the EU, the Central Asia countries, and Russia, the country has been demonstrating a growing GDP about 10% for several years now.

A buffer zone with pro-neutrality position from the Arctic to the Black Sea would have been the best outcome for European stability. The strategic independence with the pro-neutrality policy has a promising future. Many nations enjoy the necessary preconditions for the policy and are more and more clear that they see the advantages of it. Who knows, perhaps the superpowers, in an accession of rationality, will come to see that buffer states with the neutrality status are in their interest too.

Contemporary Indian thinker and scholar Sandeep Waslekar, author of the bestselling book "World Without War," consider neutrality in today’s world as essential. He advocates the creation of a Council of Neutral Nations within the United Nations. Its primary role would be to mediate conflicts between major powers. Neutral countries, more interested in their own independence than in the struggle for global domination, are better suited to put forward reasonable proposals.

How can such a coalition be formed? Governments around the world have so far shown little resolve on the issue of peace. Should civil society take a role in fostering this process and providing inspiration in building an Alliance of neutral states? A global consciousness is emerging aimed at promoting the common good and peace.https://www.vision-gt.eu/publications1/analytical-dossier/life-in-the-buffer-zones-and-neutrality-alliance/

Ambassador Brunson McKinley is a retired American Foreign Service officer with numerous posts in Europe, Asia and the Americas. In 1998 he settled in Geneva as Director General of the International Organization for Migration and has remained there as an independent foreign policy analyst.

Katy Cojuhari is a civil diplomacy professional with 20 years of journalistic background, the author of the book “Building Peace: Moldova&Switzerland “, co-founder of the Geneva Center for Neutrality.

.jpg)

During the Belgrade Security Conference, the roundtable “Lessons from Swiss Neutrality: Trustbuilding and Dialogue in the Western Balkans” explored how Switzerland’s experience in neutrality can inform peacebuilding and reconciliation in the region.

Switzerland’s long-standing tradition of neutrality has shaped its global role in diplomacy, mediation, and peacebuilding. This roundtable examined how the core principles of Swiss neutrality – credibility, discretion, and inclusivity – can support reconciliation and institution-building efforts in the Western Balkans. Participants discussed how neutrality, as both a value and operational practice, can help build trust, facilitate dialogue, and strengthen resilience in divided societies.

The session also considered how adaptable the Swiss model is to the current political and social realities of the region. Key questions included: What makes Swiss neutrality a credible and sustainable peacebuilding model? How can its principles be applied to Western Balkan dynamics? What lessons from Switzerland’s mediation and “good offices” can support regional dialogue? Where are the limits of neutrality in deeply polarized environments, and how can they be managed? And how can neutral facilitation contribute to rebuilding trust and strengthening institutional resilience across the region?

Jean-Daniel Ruch, former Ambassador of Switzerland to Serbia, spoke about the Swiss model of neutrality and its foundations. He emphasized that neutrality is not the same as non-alignment, but rather the outcome of specific historical circumstances faced by countries positioned between major powers. He highlighted the importance of neutrality being recognized by others and noted that Switzerland was fortunate to have its neutrality acknowledged more than 200 years ago.

Throughout the discussion, Ruch explored how Serbia could potentially integrate elements of the Swiss model. He pointed to student protests as an example of direct diplomacy in action. He also noted that Serbia’s position, situated between four major powers, could be leveraged as a strategic advantage—but doing so requires flexibility and significant resource investment. One remark that drew particular attention was his suggestion that the next Trump-Putin meeting could be held at Sava Centar.

Alexandra Matas, Director of the International Security Dialogue Department at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, stressed that today’s polarized world urgently needs “bridgemakers.” She emphasized that neutrality is not passivity; on the contrary, successful neutrality requires proactive engagement. Neutral countries act as facilitators, maintain backchannel communications, and do whatever is necessary to keep dialogue alive. Addressing audience questions, she highlighted the distinction between mediation, negotiation, and dialogue facilitation. She also sparked debate by suggesting that Serbia could potentially pursue both neutrality and EU accession simultaneously.

Nicolas Ramseier, President and Co-Founder of the Geneva Center for Neutrality, discussed the prerequisites for successful neutrality. He highlighted the importance of internal stability, a strong reputation, and historical credibility. Ramseier suggested that Serbia could benefit more from being a partner to the EU rather than a full member, describing this approach as “not putting all your eggs in one basket.” He envisioned Serbia as a potential diplomatic powerhouse, equipped with the tools to achieve this if the government chooses that path. On the ethical dimensions of neutrality, he stressed the need for consistent criteria and prioritizing actions that benefit the broader international community.

Moderator Lejla Mazić concluded the session by emphasizing that neutrality is a social necessity. She argued that with sufficient resources, reputation, independence, political will, and support grounded in facts and history, neutrality could become a viable reality in the Balkans. https://belgradesecurityconference.org/swiss-neutrality-and-peacebuilding-in-the-balkans-lessons-for-regional-dialogue/

Swiss neutrality is at the heart of a new think tank in Geneva and the subject of an upcoming referendum. In a world marked by increasing fragmentation, the Swiss remain deeply attached to it.

For many, neutrality is the unshakeable bulwark that protected Switzerland from the two world wars; for others, it is merely an opportunistic fig leaf that has allowed the country to conduct business, even with the most sinister regimes.

Far from the idealized image, Switzerland's status has always been a matter of room for maneuver and realpolitik. More than simply an absence of participation in war, Swiss neutrality is in fact a legal and political framework, simultaneously perpetual, armed, and nuanced. Swiss policy interprets its framework flexibly, placing it at the service of good offices and humanitarian aid. But in a world where the lines of conflict are increasingly blurred, is this distinction between law and politics still tenable?...

It is in the midst of this current situation that the Geneva Center for Neutrality was born. Former ambassador Jean-Daniel Ruch, its co-founder, explains its purpose: "Switzerland's soft power in the world is deeply rooted in neutrality... We need to try to enhance its value," - he urges.

Full version of the article is here: https://www.letemps.ch/suisse/la-souplesse-de-la-neutralite-suisse-est-plus-que-jamais-remise-en-question

On October 26, the Austrian republic celebrated a milestone anniversary. Neutrality turned 70. What's happening with Austria's neutrality today? Is it still relevant? Is Austria moving to NATO? At the same time, the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ) wants a stricter interpretation and is pushing for members of parliament to be explicitly sworn in to neutrality in the future.

In the article “What is left of neutrality”, the authors Jürgen Streihammer and Daniel Bischof write that neutrality still resonates as a myth, but in practice, it's reaching its limits. Experts are calling for a new debate: What is left of neutrality

The reseach “The Origin and Historical Change of Austria's Neutrality” by Univ. Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Mueller from the Institute for East European History, University of Vienna gives a deep reflection on the historical origin, experience and analyses of the current situation on the Austian neutrality today.

In its almost 70 years of existence, the interpretation of Austria's neutrality has been subject to constant change. Based on current surveys, this article examines the roots of Austrian neutrality and key developmental phases of its interpretation in the international context of East-West relations. Particular attention is paid to the role of the Soviet Union as an incubator of the Austrian declaration of neutrality and a formative factor in its interpretation. In addition to internal Austrian tendencies dating back to the fall of the Habsburg Monarchy and reinvigorated by the East-West occupation of Austria after 1945, the Soviet demand for a declaration of neutrality as the price for agreeing to withdraw from Austria in 1955 represented the most important root of this movement. Initially conceived as a mere renunciation of alliances and bases, the interpretation of neutrality was subject to a continual expansion of the understanding of the duties and responsibilities of permanently neutral states in peacetime during the decades of the Cold War under the influence of intensive Soviet communication and Austrian legitimization efforts. The end of the Cold War ushered in a countermovement.

Today, the assessment is divided between experts who view neutrality as an outdated security obstacle and the broad majority of the population, who consider this status worthy of protection. The continued existence of neutrality can therefore be explained by its enormous popularity among the population and support from groups on both sides of the political spectrum.

The full version is here: “The Origin and Historical Change of Austria's Neutrality”

Multi-vector diplomacy of Kazakhstan is rooted in its history, geography and geopolitics. Landlocked, bordered by Russia and China, with strategic proximity to the EU, Middle East, and South Asia, it keeps balanced relations with East and the West, dynamically developing and playing a crucial role in regional stability. One of the efficient instruments Kazakhstan’s government actively realizes in this – democratic reforms and parliamentary diplomacy.

On the sidelines of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, on September 30, in Strasbourg, a side event titled “Kazakhstan’s path to prosperity: democratic reforms and unity through parliamentary diplomacy” drew wide attention from diplomats, parliamentarians, and think tank experts. The discussion highlighted Kazakhstan’s progress in democratic reforms, its multilateral diplomacy, and its unique role as a connector between Asia and Europe.

Speaking at the event, Maulen Ashimbayev, Chairman of the Senate of the Parliament of the Republic of Kazakhstan, emphasized the country’s commitment to strengthening democratic institutions and expanding cooperation with Europe: “The European Union remains Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner and investor, accounting for about half of all direct foreign investment in our country. Kazakhstan, in turn, is among the top three suppliers of oil to the European market, with over 70% of our oil exports directed to Europe.”

Ashimbayev underscored key reforms under President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s “Just Kazakhstan” agenda, including a one-term, seven-year presidential limit, an expanded and competitive party system, and lower thresholds for party registration. He highlighted human rights reforms, notably the abolition of the death penalty, and Kazakhstan’s efforts to foster intercultural dialogue through the Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions.

Kazakhstan’s strategic position - bordering Russia and China while maintaining strong ties with the EU, U.S., and partners across the Middle East and South Asia - underpins its pragmatic neutrality. The country plays a vital role in the Belt and Road Initiative through the “Middle Corridor,” a multimodal transport route connecting China with Europe while bypassing instability zones.

Speakers underlined the balanced approach of Kazakhstan in the foreign policy. Its pragmatic, neutral policy is positioning Kazakhstan as a key connector between Asia and Europe in trade, security, and diplomacy. Invited to participate in the event, Katy Cojuhari, Head of the international cooperation department of the Geneva Center for Neutrality commented the synergy between Kazakhstan’s parliamentary diplomacy and its multi-vector foreign policy: “Parliamentary dialogue provides an avenue for countries to establish mutual confidence, to exchange experience. In parallel, Astana’s multilateral approach ensures balance among interests and creates the conditions for open dialogue between different centres of influence. Kazakhstan continues to offer platforms for dialogue, it takes initiatives in peacebuilding and in regional integration, which reinforces stability across Eurasia and beyond”.

https://www.vision-gt.eu/news/kazakhstan-as-a-key-connector-between-asia-and-europe/

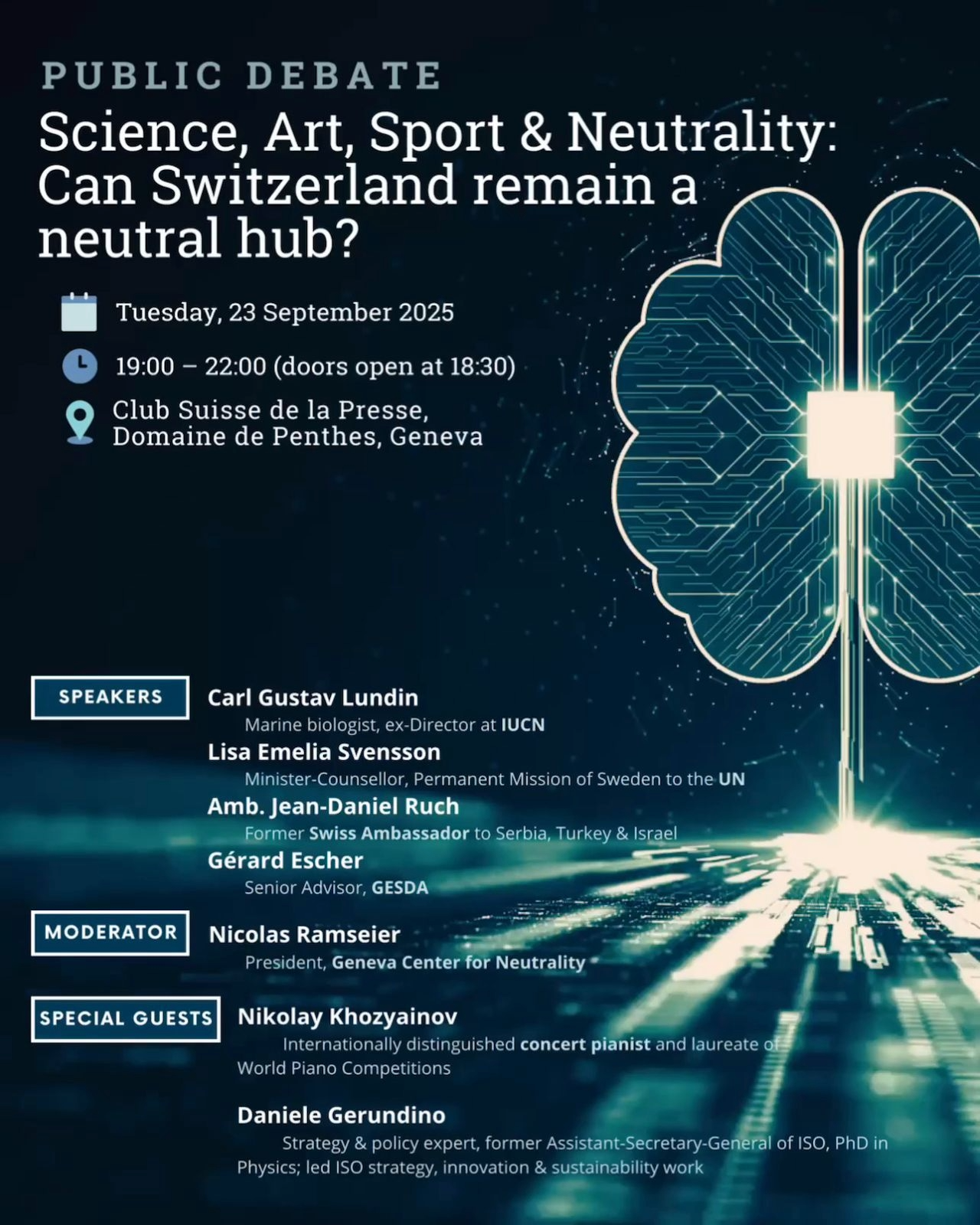

At the International Pre-Congress on Neutrality, held in Geneva in June this year, experts, academics, diplomats, and activists from 27 countries gathered to explore a pressing question: Is neutrality still possible in today’s world? Together, they examined how the principle of neutrality can be revitalized and reimagined as a tool for peace in the XXIst century.

The International Colloquium on Neutrality was convened under the auspices of the Geneva Centre for Neutrality, in collaboration with World Beyond War, the International Peace Bureau, the Transnational Institute, the Colombia Peace Agreement, the Global Veterans Peace Network (GVPN), and the Inter-University Network for Peace (REDIPAZ). A global call for active neutrality launched from Geneva reassessed and reaffirmed the value of neutrality in an increasingly polarized and militarized world.

The colloquium built upon the foundation laid at the 2024 International Congress on Neutrality in Bogotá and set the stage for the upcoming 2026 Congress. Its central outcome was Modern Neutrality Declaration and an accompanying Action Agenda to Promote Active Neutrality - documents that reflect a collective commitment to advancing neutrality as a dynamic, peace-oriented principle.

Five specialized focus groups explored key dimensions of neutrality: Current Neutrality Practices, Digital Neutrality in the Age of Cyberwarfare and AI Militarization, Neutrality and Media, Neutrality and Common Security in a Militarized World, Building a New Non-Aligned Movement. Moderators from each group collected insights, and formulated forward-looking strategies with practical recommendations, and calls to action.

GROUP 1. CURRENT NEUTRALITY PRACTICE.

Moderator – Katy Cojuhari, Head of International Cooperation Department, Geneva Center for Neutrality.

Global Neutrality in 2025:

● Europe: Neutrality is retreating, though not entirely abandoned, as alliance politics gain ground.

● Post-Soviet Space: Neutrality remains in limbo amid competing internal and external pressures.

● Asia: A nascent neutrality movement is emerging, with countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, ASEAN states, and Mongolia exploring or reaffirming non-alignment.

● South America: Costa Rica continues as a beacon of hope; several states have adopted ad-hoc neutrality during the Ukraine war.

Key Themes and Takeaways:

1.Redefining Neutrality: Neutrality is evolving beyond its legal roots, taking on political, philosophical, economic and strategic dimensions in a multipolar world. It involves a commitment to non-alignment, positive diplomacy, and legal engagement.

2. Global South Perspectives: Countries like Costa Rica exemplify a principled, demilitarized neutrality that contrasts with European models, highlighting the need for decolonizing international discourse.

3. Challenges in Europe: The retreat from neutrality in Europe, especially after the Ukraine conflict, raises concerns about militarization and the loss of alternatives to alliance politics.

4. Role of Civil Society: Grassroots movements across continents (Germany, Colombia, Australia) are advocating for neutrality as a means to prevent war and promote global stability. These efforts represent a form of “neutralism”— a normative commitment to peace without passivity.

5. Legal Complexity: The discussions underscored the legal intricacies of neutrality, especially regarding obligations under international humanitarian law versus unilateral declarations. Costa Rica, Turkmenistan, Austria and Switzerland were identified as states currently possessing internationally binding neutrality.

Key insights:

Rethinking Neutrality:

● Neutrality is not indifference. It represents an active commitment to peace, dialogue, and self-determination.

● Neutrality is not isolation. Neutral states can serve as mediators, conveners, and norm-setters in international affairs.

Diverse Models of Neutrality:

● Costa Rica: A global exemplar of legally binding, unilateral neutrality; no standing army since 1948; strictly non-aligned in moral and economic terms.

● Switzerland: Armed neutrality under pressure due to alignment with EU/U.S. sanctions; national referendum planned regarding its constitutional neutrality clause.

● Moldova: Constitutional neutrality threatened by political elites favoring NATO alignment, despite over 80% public support for neutrality.

● Austria and Ireland: Legal neutrality increasingly diluted by military cooperation with the EU and indirect NATO participation.

● Turkmenistan: UN-recognized neutrality since 1995, illustrating that neutrality is not exclusive to democratic states.

Current Risks:

● Instrumentalization of neutrality for geopolitical ends.

● Undermining neutrality through participation in economic or military sanctions, adopted or not sanctioned by the UN Security Council.

● Erosion of public trust when elite policies contradict constitutions or public sentiment.

● Absence of binding legal mechanisms at the international level to enforce or protect neutrality.

Recommendations.

Call to Action for States:

1.Clarify or codify neutrality in constitutional, legal frameworks and public debates.

2. Develop National Strategies for Peace: Invest in peaceful infrastructure not only security apparatus, including diplomacy, legal institutions, and humanitarian capacity

For Civil Society:

3. Promote neutrality through peace education, public dialogue, cultural nonalignment, conflict prevention and peaceful settlement of disputes.

4. Explain the values and benefits of neutrality through mainstream media, social media and civil society actors.

5. Create independent neutrality observatories to monitor state actions.

6. Support various neutrality initiatives (especially International Neutrality Day on 12th of December and UN resolutions related to neutrality) through grassroots campaigns, referenda, and public discourse.

The creation of an International Neutrality Platform, created at International Pre-Congress on Neutrality:

7. Convene an International Congress for Neutrality bringing together states, experts, and civil society actors.

8. Develop and launch a Global Neutrality Database to benchmark legal, policy, and perception-based aspects of neutrality.

9. Draft and promote a Model Charter of 21st Century Neutrality for voluntary adoption by states, civil society and by the United Nations.

GROUP2. DIGITAL NEUTRALITY IN THE AGE OF CYBER WARFARE AND AI MILITARIZATION

Moderator – Simon Janin, Digital Neutrality Department, Geneva Center for Neutrality.

PART 1. Digital Neutrality and Challenges.

Digital neutrality is defined as a nation’s ability to safeguard its digital infrastructure, data governance, and artificial intelligence (AI) systems from foreign manipulation or influence, ensuring autonomy in digital spaces. This autonomy is critical for maintaining a country's sovereignty, preventing populations from being let into conflicts against their interest, and preserving the democratic ability to determine their future. In today’s world, major corporations frequently function as extensions of geopolitical strategies, with their platforms becoming militarized tools of influence. Examples include: data-driven political manipulation and disinformation campaigns vis social media; surveillance infrastructure and AI-based automated systems that can be weaponized for mass control or conflict escalation.

Policy Recommendations:

- Advocate for a United Nations Declaration on Active Neutrality including digital and cyber neutrality.

- Develop national and regional frameworks to regulate AI and autonomous weapons systems.

- Launch the Digital Neutrality Label project, which will be proposed as a Geneva standard for countries and organizations seeking a sustainable and secure digital future.

- Establish institutional alliances among civil society and government actors engaged in active neutrality worldwide.

Strategic Alliances. Collaborations should actively involve: universities and research institutes; International think-tanks and NGOs; Technology-focused civil society groups; Relevant international organizations (UN, UNESCO, OECD).

PART 2. Cyberspace and AI.

1. Active Neutrality:

○ Neutrality must be actively promoted and defended, as cyberspace is dynamic and actors constantly seek to exploit or undermine neutral stances.

○ Passive neutrality is insufficient given the proactive threats in cyberspace.

2. Attribution Challenges:

○ Estblishing accountability in cyberspace is inherently difficult due to technological complexity, dual-use nature of tools, and the role of non-state actors.

○ Precise attribution of cyber attacks is often challenging, complicating enforcement and response.

3. International Norms and Treaties:

Currently, there is no binding international legal framework specifically addressing digital neutrality or AI militarization. Proposal includes clear international norms, legally binding treaties, and diplomatic agreements specific to cyberspace and AI.

4. Switzerland's Role in International Law:

○ Switzerland should leverage its neutrality tradition and global reputation to lead discussions and possibly establish certification standards and ethical governance guidelines for AI, particularly military applications.

○ Switzerland could serve as a model country for digital neutrality, providing frameworks for technology governance and attracting global partnerships.

5. Startup and Innovation Ecosystem:

Switzerland should foster Silicon Valley-style ecosystems with strong network effects under special regulatory frameworks or sandboxes. The creation of agile, adaptable legal frameworks can encourage innovation, investment, and technological growth without compromising broader regulatory standards.

6. Decentralized Systems and Practical Steps:

Encouragement of decentralized payment and information exchange systems as demonstrated by practical, government independent technological innovations (e.g., transactions in space).

7. Neutrality Advocacy in Big Tech:

○ Promote neutrality through internal advocacy within Big Tech, challenging technological support for militarization or unethical applications of technology.

○ Focus public awareness campaigns on the importance and practicality of active neutrality, peace, and diplomacy as viable alternatives to militarization.

8. Counteracting Propaganda: Actively counter propaganda from military alliances which seeks to portray militarization as progressive or necessary.

9. Incremental and Pragmatic Implementation:

○ Adopt an entrepreneurial mindset—implementing quick, pragmatic steps that can adapt rapidly to technological and geopolitical changes.

○ Establish a clear roadmap with small targets and scalable successes that build toward larger neutrality goals.

10. Interdisciplinary and International Collaboration:

○ Actively facilitate interdisciplinary expert discussions involving legal, technological, ethical, and business perspectives.

○ Prioritize international collaboration to create consensus- driven definitions, norms, and enforcement mechanisms.

Conclusion.

Switzerland has a unique opportunity to lead in shaping active digital neutrality and ethical AI governance by leveraging its historical neutrality, technological expertise, and robust legal frameworks. The creation of specialized innovation ecosystems and international treaties is essential to navigate the complexities of modern cyberspace effectively.

GROUP 3. NEUTRALITY AND THE MEDIA

Moderator – Tim Pluta, Global Veterans Peace Network.

Current Challenges and Observations:

1. Political Bias in Media.

Media often aligns with existing imbalances in power structures, reinforcing political agendas and deepening social divisions.

2. Manipulation of Public Sentiment.

There is a growing disconnect between political actions and the will of the people. Media is frequently used to manipulate emotions by spreading fear, hatred, and polarising narratives.

3. Monopoly on Truth.

Mainstream media tends to present itself as the sole authority on truth, marginalising alternative perspectives and voices.

Proposals and Recommendations:

1. Awareness & Culture.

• Create awareness and foster a culture of curiosity around active neutrality and its societal benefits.

• Promote the use of the term “active neutrality” in public and private conversations to normalize and expand understanding.

2. Education & Guidelines.

• Develop a neutrality vocabulary and curriculum tailored to various audiences (politicians, activists, educators, general public etc.).

• Create an educational program that defines active neutrality in political, legal, social, and even spiritual terms.

• Provide recommendations to media professionals to encourage pluralism and eliminate dehumanizing language, fear-mongering, and hate speech.

3. Platforms & Engagement.

• Launch an open, decentralized platform or news channel focused on active neutrality.

• Establish citizen journalism initiatives and online communities centered on neutral reporting and civic media literacy.

• Include media representatives in dialogue circles on active neutrality.

• Conduct public surveys to explore how people perceive active neutrality and whether they value it.

Institutional Strategy:

We propose forming an Active Neutrality Media Expert Team under the Geneva Center for Neutrality, composed of: social media specialists, psychologists and neuro-linguists, youth representatives, journalists, IT-specialists, etc.

This interdisciplinary team would interact to:

• Develop a strategic media campaign around active neutrality;

• Design and implement educational initiatives;

• Foster youth engagement in the media and peace narrative.

To paraphrase Barbara Marx Hubbard, we believe: “We need a neutral media room as sophisticated as the war media room.” This report is a collective call to bring active neutrality to the table — not only as a principle but as a practice embedded in how we inform, educate, and engage society.

GROUP 4. NEUTRALITY AND COMMON SECURITY IN A MILITARIZED WORLD.

Moderator – Emily Molinari, Deputy Executive Director at the International Peace Bureau.

Introduction

This focus group explored the relevance and application of neutrality and common security in today’s increasingly militarized geopolitical landscape.

Key Themes:

1. Redefining Neutrality

Neutrality should not mean silence or inaction. Participants emphasized the need for a new model of engaged neutrality; it must uphold peace, human rights, and international law. Switzerland was often cited, though its model of “armed neutrality” was challenged as contradictory.

2. Legal Dimensions

Neutrality is rooted in customary international law, but remains fragile in the context of the UN’s collective security system. Key legal principles include: non-participation in conflict and impartiality; maintenance of economic relations (excluding arms trade); obligation to avoid escalation and allow humanitarian aid; engagement in diplomacy, mediation, and good offices. Participants discussed whether a binding treaty on neutrality could strengthen these norms.

3. Common Security Framework

Common security — mutual, cooperative security — was reaffirmed as an alternative to deterrence and arms races. It relies on disarmament, trust, and diplomacy. The group stressed links between common security, social justice, and climate resilience.

4. Economic Neutrality, Militarization, and Sovereignty

Neutrality must extend beyond military alliances to economic structures: reduce dependence on arms industries and extractive economies; oppose coercive trade practices by great powers; strengthen economic sovereignty, especially in the Global South. Militarization undermines national and community sovereignty. Neutral states are often pressured into alliances or bloc politics, eroding their impartial roles. Some participants criticized NATO expansion, hybrid threats, and economic coercion.

5. Private Sector & Media

Participants noted that militarism is often supported by business and media, while peace work remains under-resourced. Proposals included: fostering a peace economy and ethical business practices; promoting peace-oriented journalism; countering disinformation and propaganda.

Illustrative Cases and Proposals:

- Costa Rica: A key example of successful demilitarization — post-military investment in education and healthcare helped anchor its neutral, peaceful stance.

- Switzerland: Raised internal tensions around armed neutrality and civil disobedience (e.g. CO debates, TPNW campaign).

- Non-state actors: Movements like MINGA and ISM illustrate the role of grassroots solidarity in peacebuilding.

- New ideas: Proposals included the creation of a “Neutrality Observatory” to monitor violations and a business-peacebuilding network to promote ethical alternatives.

Recommendations:

- Promote engaged neutrality as a proactive and legitimate framework for peace and diplomacy across all actors.

- Open discussion on neutrality concerning autonomous groups, territories, and minority populations, recognizing their unique positions and challenges.

- Highlight the benefits of neutrality for States:

- Not being involved in conflict, being protected from it, and maintaining economic relations with all parties involved in a conflict.

- Credibly exercise the duty of impartiality, meaning treating all conflict parties equally and refraining from influencing the conflict’s outcome.

- Encourage neutrals to actively engage in humanitarian aid, diplomacy, mediation, and good offices, leveraging their impartial status for constructive involvement.

- Support initiatives calling for reductions in global military spending, strengthening arms control and disarmament treaties, and reinvesting those resources into social welfare, climate action, and peace infrastructure.

- Advance economic neutrality, encouraging states to divest from the military-industrial complex, invest in human security, and prioritize economic sovereignty, especially in the Global South.

- Invest in nonviolent civilian defense strategies, such as: civil resistance training; peace education programs; support for conscientious objectors; development of national institutions dedicated to disarmament and peacebuilding.

- Possibility to foster cooperation between peace organizations and some actors of the private sector, including the creation of a peace economy network and incentives for ethical business practices aligned with peace and sustainability goals.

- Establish a Neutrality Observatory to: monitor violations of neutrality and international law; produce independent reports; support advocacy at the UN, EU, and regional bodies.

- Strengthen critical journalism and media literacy by supporting disinformation monitoring initiatives, promoting independent, peace-oriented reporting, and raising public awareness on the links between militarization, media, and public opinion.

GROUP 5. BUILDING A NEW NON-ALIGNED MOVEMENT.

Moderator – Gabriel Aguirre, coordinator of the international Congress for Neutrality (Colombia), South American branch of the World Beyond War.

1. Purpose of the Meeting

This focus group was convened to explore the possibility of a new Non-Aligned Movement beyond the traditional state-based model. A global civil society-centred approach was proposed, with a view to building tools for peace and social justice in the context of current conflicts and systemic crises.

2. Criticisms of the Traditional Model of Non-Alignment.

a. The term "non-aligned" is seen by many participants as obsolete, inherited from the Cold War, so we suggest not speaking of Non-Aligned, but of Active Neutrality.

b. Its usefulness is questioned in the face of a contemporary multipolar world, where conflicts are no longer explained solely in terms of East vs. West.

c. It is proposed to replace the notion of “state neutrality” with people’s diplomacy.

3. Emerging Key Themes.

a. People's Diplomacy:

● A form of diplomacy is promoted that does not depend on governments or state interests.

● An international network is being sought that brings together social organizations, communities, indigenous peoples, and grassroots movements to address militarization, colonialism, and the climate crisis.

b. Criticisms of Global Militarization:

● Military spending is denounced as the most polluting activity on the planet.

● Multiple conflicts, especially in Palestine and Ukraine, are identified as examples of the failure of the current international system and the urgent need for a global ceasefire.

c. Rights of Future Generations:

● defence of future generations is incorporated as a new axis of international political thought.

● It is mentioned that this approach must include ecological, climate and intergenerational justice rights.

● Defending plurality is understood as an important value, in order to respect the views of others, not just those of a particular individual, and thus respect diversity, in order to overcome racism and xenophobia.

d. Reparations and historical justice

Participants from Africa and Latin America spoke about the need for reparations for the historical damage caused by colonialism, wars, and unilateral economic sanctions that continue to affect entire populations.

4. Cases Analysed.

Palestine: Considered a symbol of modern genocide and the moral failure of the international community. It is argued that a simple ceasefire is not sufficient if there is no active pressure for lasting justice.

Colombia: The armed conflict and peace agreements are analyzed from a structural perspective. It is emphasized that without social justice, the end of armed violence will not be sustainable.

Venezuela: Economic sanctions are denounced as a form of indirect warfare, with devastating effects on the civilian population, especially on health and nutrition.

5. Strategic Proposals.

a. Promote modern neutrality as defender of sovereignty and uphold the principle of non-alignment.

b. Reshape the international system, beyond the UN and the States.

c. Create a decentralized, non-hierarchical and plural movement.

d. Focus on peace, demilitarization, decolonization and self-determination.

e. Develop a proactive narrative of neutrality as action for peace, not passivity.

f. Defend Active Neutrality to build bridges between peoples, with the fundamental role of civil society.

Conclusion

The group proposed building a new international paradigm from below, where neutrality is not indifference, but an ethical stance in the face of injustice. It aims to articulate a grassroots transnational movement focused on nonviolent action, global justice, environmental sustainability, and the self-determination of peoples. Neutrality should not be understood under a double standard; it should be applied equally to all countries, social movements, communities, etc.

The International Colloquium on Neutrality: A call to action for active neutrality and world peace, 26th and 27th of June, 2025.

.jpg)

The comprehensive analysis by Dr. Edward Horgan, an Irish peace activist and former army commandant, presents a deeply researched and passionate case for positive, active neutrality as a viable and necessary alternative to militarism and war in the 21st century.

Drawing from history, international law, Irish constitutional principles, and moral philosophy, the author critiques Ireland’s drift from neutrality—especially through US military use of Shannon Airport, complicity in war crimes, and proposed abandonment of the Triple Lock (government, Dáil, and UN approval for military missions). Horgan argues that such shifts endanger Irish sovereignty, violate international humanitarian law, and make Ireland complicit in global violence.

The research also highlights:

- The history and types of neutrality (constitutional, active, default, etc.);

- The erosion of the UN and EU as peace-building institutions;

- The environmental and human costs of global militarism;

- Ireland’s role in UN peacekeeping and the potential of unarmed civilian peacekeeping;

- The global legal frameworks (e.g., Hague, Geneva, Genocide Conventions) being undermined by powerful states.

Horgan makes a compelling ethical and legal argument that active neutrality, grounded in international law and humanitarian values, should be central to Ireland’s identity and foreign policy—and part of a broader global movement for peace, justice, and demilitarization.

Full version: NEUTRALITY FOR PEACE AND HUMANITY ALTERNATIVE TO MILITARISM AND WAR

By Dr. Edward Horgan, a former Irish Army commandant, who served with UN peacekeeping missions in Cyprus and the Middle East in the 1960s and 1970s. He is a committed peace activist with Shannonwatch, member of the Irish Peace and Neutrality Alliance, founder member of Veterans For Peace Ireland, and Veterans Global Peace Network, and member of the board of directors of World Beyond War.

Discussed during the International Colloquium on Neutrality: A call to action for active neutrality and world peace, 26th and 27th of June, 2025.

Switzerland along its long history has experienced different, interactive and evolving kinds of neutrality. In their first Alliance Convention (1291) the three cantons’ representatives introduced the duty for them to refrain from participating in disputes of the other, but to encourage and help them to achieve amicable agreement. The objective is to preserve the inside security and unity.

Soon joined during the next centuries by other cantons, the successive Alliance Conventions were concluded each time with the same approach : the duty to refrain from participating in the internal dispute inside the Alliance is conceived to protected this union. The third and not implicated canton is invited to « mediate », in order to reestablish interior peace and avoid external intervention. Neutrality linked with mediation has a (self)protection objective (passive neutrality). This idea was more developed when Basel Canton joined the Alliance (1501) : the duty to refrain from participating in dispute is clearly connected with the duty to intervene as a third party to find amicable solution. Moreover, Basel was called to « mediate » a dispute between a canton member of the union, Bern, and a non-member at the time, Geneva, and they reach an effective and sustainable agreement, after negotiations facilitated by the third (a Basel representative ; le Départ de Bâle de 1544). It looks like a first esquisse of the pacification objective, which developed as the active neutrality during the decades following the second world war.

The intercantonal Agreement called « Le Défensional de Wil » (1647) forbids the cantons to intervene militarily also outside of the Alliance, in the dispute between other Countries. The aim was to avoid though neutrality and independence external interferences and to protect against themselves. Refraining from participating into the 30 Years War (1618-1648), the cantons preserved at the same time external intervention and internal disputes, sparing a lot of population slaughters, cities, crops, harvests and other unlimited destructions, and losses of territories. This objective of protection was reflected also in the peace treaties of Paris and Vienna (1815) which recognised the Swiss neutrality and independence in the interest of Europa and Switzerland. That was also the common objective of the Parties to these treaties and of Swiss Cantons.

This neutrality of protection was completed by the neutrality of pacification (or active neutrality) after 1945 till the years 2010, with the Swiss Good Offices : Evian Agreement (1962 Algeria independence), first conflicts between USA and Iran, Russia and Georgia, Geneva Initiative (2003, facilitate a two-States peace plan), and encouraging mediations in internal armed conflicts in South America and Africa.

Contributing to build the peace was the Swiss software. But this constructive practice of neutrality seems having lost its importance this last decade for Swiss Authorities. Trough outside and inside pressures it have been few and few put in drawers, in the frame of the events in East Europa as of 2014 and in the Middle East.

The need of security prevails among Swiss Authorities. Thus, they introduced new practices and ideas, with an « original » new concept of neutrality : a so called cooperative neutrality, implying several agreements concluded with the NATO. An oxymoron ! Though it might have and has of course an impact on the trust in Switzerland, perceived as a country having lost or suspended its neutrality and independence.

For the Swiss Authorities, independence and neutrality are political and legal concepts, which should or could be adapted in practice to new situations, whilst for a broad part of the Swiss people they are values, that are part of the identity of the country. What is the perception of other countries about such changing? Will Switzerland deserve the trust from other nations for further mediations, good offices and other amicable facilitations? Will Geneva remain a place for peace negotiations, humanitarian law and disarmament conferences? But also are the Swiss Authorities themselves still willing to be actively implied in amicable processes to preserve or reestablish the peace?

CONCLUSIONS : A SMALL ROOM FOR A GREAT DREAM

On the level of the ideas, neutrality does not seem compatible with dualist visions of the world supported by totalitarian Manichean ideologies, which divide the countries in two camps: the Good and the Evil, the democracies and the democratures, the Nord and the South. In a recent interview[1], Professor Pierre Blanc gives another analysis, distinguishing two movements : a necessity of regulation on one hand and a predation hubris on the other hand, with the conclusion that « the balance of power can not be favourable to predators States » because « their attitude is under the fire of criticism which increases in intensity »… « The world is shared between predators’ appetites and a thirst of regulation. But also between authoritarian excesses and requests for emancipation. » This analysis is fully compatible with a place for peace through mediation and other amicable approaches. It belongs therefore to Independent and Neutral Institutions and States to make sure the switch goes in the right way. Beginning by unifying their efforts to make possible the development and implementation of peace through mediation and other kinds of amicable processes, for instance in the frame of the Geneva Center for Neutrality.

[1] Pierre Blanc, « Les effets du multilatéralisme environnemental sont déjà là », Le Monde, Entretien, 15.06.25 page 8

Full vertion of the research: Peace through mediation: a challenge. Is there a room for efficient and sustainable peace agreements ?

By Jean A. Mirimanoff, Independent Mediator (FSM/SFM), Honorary Magistrate, former ICRC Legal Adviser

For Neutrality Colloquium: A Call to Action for Active Neutrality & World Peace, Geneva, 26–27 June 2025

On June 26 and 27, an International Colloquium was held in Geneva on the theme “A Call for Action for Active Neutrality for World Peace.”

The symposium brought together nearly 90 participants, from 27 countries representing all continents. Held under the auspices of the Geneva Center for Neutrality (GCN), the symposium marked a pivotal step in the global effort to redefine the role of neutrality in the 21st century. It followed the 2024 International Congress on Neutrality in Bogotá and served as the International pre-Congress for Neutrlaity for the next Congress planned for 2026 — with Geneva among the potential host cities.

The participants agreed on a declaration listing the current challenges to world peace, as well as an action plan that includes

- Promoting the principle of neutrality as a form of active peacebuilding.

- Building global platforms of action to stop war, reclaiming the important role of neutrality. In this context, we are launching an international network of actors committed to neutrality, acting also as a permanent observatory of global neutrality practices.

- Drafting a United Nations declaration on active neutrality in the digital and cybersphere, with the goal of achieving international treaty on neutrality in the digital age, ensuring a lasting normative framework for digital peace.

- Launching a Swiss Digital Neutrality Label, a new benchmark for nations and organizations striving for trusted, secure, and resilient digital ecosystems.

- Claiming sovereignty and non-alignment as referents of neutrality

This ambitious agenda was shaped with the contribution of leading experts in diplomacy, cybersecurity, international law, and digital governance, who were specifically invited to explore innovative pathways toward technological neutrality and sovereign digital infrastructure.

The participants see neutrality as the cornerstone of a global governance framework that harmonizes the imperatives of peace, climate, and development.

Modern Neutrality Final Declaration

Action Agenda to Promote Active Neutrality

What is the key to a secure and peaceful future? Like its neighbor, Moldova and the breakaway region of Transnistria are ethnically diverse, complicating questions of national sentiment and strategic alignment... Moldova's best option at this critical juncture in the world's geopolitical evolution would be to formally declare its intention to remain neutral. With tensions between East and West resurfacing, it makes sense to expand the buffer zone...

https://www.letemps.ch/opinions/moldavie-eviter-de-devenir-une-nouvelle-ukraine

American tech giants are invoking the Chinese specter to avoid any regulation. Yet the United States enjoys a massive advantage in computing power, energy, and talent.

For some time now, a narrative has taken hold in Western capitals, particularly in the United States. We are repeatedly told that the West is engaged in a frantic race against China to dominate artificial intelligence, and that losing this race would have catastrophic consequences for our societies and values. This narrative is simple, anxiety-inducing, and effective—but it contains a major flaw: it does not reflect the global technological reality. Instead, it may serve other interests.

First, let us try to understand where we stand. According to several studies, including those by D. Kokotajlo, progress in AI rests on three pillars. The first is “compute,” the raw computing capacity required to train advanced models. The second is access to abundant and stable energy, since each new generation of models consumes ever-increasing amounts of electricity. The third is human talent, indispensable for designing, fine-tuning, and supervising these systems. Without compute, no models. Without energy, no compute. Without talent, no progress. And on all three pillars, the United States currently enjoys a massive structural advantage.

Artificial intelligence

The United States possesses roughly five times more computing power than China, largely thanks to Taiwan, where TSMC manufactures the world’s most advanced chips using American equipment. Without these components, China cannot train comparable models. The American advantage also rests on energy. Its vast energy mix allows it to power data centers at costs well below those of China or Europe. The United States also has underutilized gas power plants that can be mobilized quickly. China, by contrast, remains constrained by local grid saturation and a heavy reliance on coal. As for talent, leading AI researchers are primarily based in the United States, which attracts top profiles trained in Europe, India, or China.

U.S. tech leaders speak of an existential threat and claim that any regulation would mean losing the race, while deploying massive lobbying efforts. This rhetoric is not without echoes of the Cold War, when the military-industrial complex amplified Soviet power to secure budgets. Presenting AI as vital makes it possible to capture public contracts while weakening democratic safeguards.

The confrontation is less between Washington and Beijing than between industry giants and democratic institutions. In California, the ambitious SB 1047 bill was buried under industry pressure and replaced by the TFAIA (Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act), a hollowed-out version that changes almost nothing in corporate practices. Yet the risks are real. Industry leaders themselves acknowledge that an uncontrolled AI could threaten global security, with Sam Altman even evoking an extinction-level risk. How, then, can a strategy that accelerates this race while undermining democracy be justified?

Switzerland does not need to imitate U.S. deregulation or Asian rigidity. It can choose a clear technological path: invest in compute, secure energy supplies, attract talent, independently test models, and require a minimum level of transparency. This is how an open and liberal country can regulate AI without stifling it—by strengthening both trust and innovation.Et si la vraie menace de l’IA ne venait pas de «l’autre»?

Guest contributor: Nicolas Ramseier, President of the Geneva Center for Neutrality.

On December 12, marking the International Day of Neutrality, the International Institute for Global Analyses released an overview in its Analytical Dossier, examining contemporary world dynamics with particular attention to the concept of neutrality: Life in the «buffer zones» and Neutrality Alliance

Is Trump relying on a form of transactional diplomacy aimed at engaging China and Russia in a global governance system shaped primarily by the interests of these three major powers? It looks like the consensus among them has yet to be reached. Medium-sized states are scrambling to balance relations with all three powers, hoping to protect their vital national interests. Small states, especially those stranded in geopolitical buffer zones, have it even worse: being forced to choose sides. In this polarization, countries with traditions of neutrality, and those now adopting pro-neutrality policy as a survival strategy, are becoming more and more important.

Swiss neutrality: questioned, but not lost

The Swiss version of neutrality is often held up as an example for other nations to follow – those that do not wish to be absorbed into the spheres of influence of one of the three superpowers. Swiss neutrality was born in the middle ages through a combination of geography and the independent spirit of the country’s citizens. Powerful monarchies on all sides could have overwhelmed the Helvetians but did not believe the prize was worth the effort it would have taken to break Swiss spirit. While never rich in those early days, Switzerland provided a trading hub and a source of military manpower for its big neighbors and managed to survive independently of the European empires.

Switzerland’s status as a formally neutral state was strongly reinforced at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when the European powers and Russia, decided that it would be in their own interest and in the interest of the concert of Europe to insist on and codify Swiss neutrality, keeping Switzerland out of the hands of rivals and providing for a space free from their continuing competition. The decision to attach Geneva to the Confederation in 1815 added over time several important new dimensions to Swiss neutrality – an openness to refugees, a safe space for savants, a focus on humanitarian action, conventions and institutions that grew into a would-be supranational system of world governance, intergovernmental arbitration, multilateralism writ large and, most visibly, a home for what was designed to be the first world government, the League of Nations.

It was not just Geneva. By the end of the nineteenth century, hydroelectric power kick-started Swiss industry. Switzerland’s determination to be able to defend itself against all potential enemies led in time to a vigorous arms export sector – tous azimuths. The Federal government early on went into the business of providing “good offices” to maintain communication between mutually hostile states. Zurich contributed bank secrecy. The Cold War enhanced the role of Switzerland, especially Geneva, as the meeting place of great powers.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, Swiss neutrality has suffered severe blows. Superpower competition is no longer confined to Europe. Europe, including Switzerland, has tucked itself under the wing of the Americans, the same Americans whose attention has shifted toward China and a reemergent Russia. Switzerland finds itself not at the neutral center of competing powers but incorporated into one of them – the West. Bank secrecy has been partly abolished. The arms trade is curtailed. Multilateralism and the institutions that embody it are increasingly discredited. Respect for humanitarian law has become an attribute of small states, while the big ones prefer Realpolitik. Some Swiss favor joining the European Union and in any case follow the EU lead, as in sanctioning Russia. At the same time, other countries are stepping up as rivals in the business of facilitating dialogue. To be sure, all is not lost. Some Swiss are trying to hang on their neutrality and even enhance it. One of the examples - through becoming a neutral hub for data storage. The arc of Swiss neutrality – a noble history and tradition, what it might means in the twenty-first century context? Much will be decided by a national referendum in near future on Switzerland's neutrality.

Strategic independence with the neutrality elements

Today, all around the world, many countries are seeking to avoid having to join one superpower block. They aspire trying to reach the strategic independence – non-alignment, with pro-neutrality elements. But the option is not available to every country. Those that lie squarely within the sphere of influence of a superpower will be obliged to follow its lead, happily or grudgingly. Costa Rica, who is neutral by Constitution, for example, is free to state its aspirations but will be compelled to yield to the United States on any important strategic question. The same applies to Belarus vis-à-vis Russia or North Korea vis-à-vis China.

The nations that can legitimately hope for strategic independence are those that lie between the spheres of influence of the superpowers and try to write their own foreign policies, within limits, by playing off the superpowers and acting as a buffer between them.

India has been playing the game of strategic independence since 1947 and is likely to continue on this non-alignment line. Its traditional ties to Russia are still strong and Modi has worked for better relations with both the USA and China. Because of its size and growing wealth, India may be tempted to enter the ranks of the superpowers, but it will confront two major problems if it pursues that strategy – the fierce opposition of Pakistan to any Indian moves that would further tilt the balance of power in the subcontinent and the resistance of the Big Three to allowing India to amass the large nuclear arsenal that is a necessary component of superpower status.

The Near and Middle East has been for centuries a focal point of major power rivalry. Today the Big Three all seem to be on a different line. While hoping to exploit the wealth of the region economically, neither the USA, nor China, nor Russia seems inclined to operate geo-strategically in the region any longer than some may have to. Rather all three seem to want influence and trade without responsibility or reckless desire for change. This means that once Israel is protected by the Abraham Accords, the region should be free to pursue strategic independence, tailoring its relationships to the superpowers to fit its own interests. Interestingly, this same logic could soon apply to Iran, to whom the idea of neutrality is not acceptable today, but for the future may serve as the solution for it and for China, USA and Russia. Same for Lebanon, where the idea of neutrality seems to be utopian today, but there are forces, straggling for it now. Already China and Saudi Arabia are dealing with each other in ways that would have been inconceivable only a few years ago, and pragmatic neutrality appeared in the international vocabular today. Qatar has become a major locus of diplomacy and mediation, along the lines of the Swiss model, but at the same time hosts a major US military base, not really consistent with the Swiss pattern of neutrality, but compatible with strategic independence. The UAE would like to emulate Qatar.